Togo and the (Golden) Iditarod Trail

Togo on the shoulders of his musher, Leonhard Seppala in Alaska.

There is a chance you may have watched or at least heard about the new Disney movie “Togo” that tells the story of the sled dog Togo and the Serum Run in 1925 that had life-saving serum brought across Alaska to Nome by dog-team to save hundreds of lives from deadly diphtheria.

While some of this heroic journey indeed took place on part of what we today know as the Iditarod race trail, contrary to popular belief, the Iditarod race was not actually established to commemorate the actual Serum Run!

Now, the 20 dog teams that took part in the relay to deliver the serum from Nenana to Nome, were dog teams out of the villages that almost all took part in the delivery of mail and freight on the trails. And it is indeed these dogs, the tradition of freight by dog team and the trail system that they used that the Iditarod race commemorates!

Today the town of Iditarod is a ghost town, except when the only standing, functional building becomes the checkpoint of Iditarod during the Iditarod sled dog race! Credit: Mille Porsild – http://facebook.com/RunningSleddogs

Around year 1900 tremendous amounts of gold had been found in Nome on the coast of Alaska and in the Yukon in Canada, but the interior of Alaska had not seen much of the arrival of the gold rush and prospectors from down south, yet. That changed on Christmas Day in 1908 when gold was struck in the heart of Alaska. It was ‘the middle of no-where’ but two years later Iditarod port and town was established and some 10,000 tons of equipment and more than 10,000 men looking for riches arrived with thousands to follow, heading for what was now the town of Flat ‘up and over the hill’ where the gold was found. The rivers here are so shallow that barging is not easily feasible as well as very limited and risky.

The Dena’ina and Deg Hit’an Athabascan peoples native to the region had trails all over this interior area of Alaska, for eons – just like the Yupik and Inupiaq natives did along the Alaskan coastline. But the trails were not all connected into a ‘delivery system.’ With this sudden heavy traffic and need for freighting, came the call for an established trail to get supplies and mail easier and more frequent to and from Iditarod to Alaska’s ice free port in Seward and to the port in Nome. Thus the Alaska Road Commision sent out a team of four men supported by dog teams in 1908 to survey and establish “a trail” connecting and expanding on what already existed. That became the Iditarod Trail, also known as Seward-to-Nome.

$125000 worth of gold bricks in found and melted in Iditarod, Alaska.

Today this trail is named the Iditarod National Historic Trail. It is Alaska’s only National Trail, it is America’s last Great Gold Rush trail, it is the only winter trail, and it is the only National Trail in the US dedicated to “man’s best friend”—the sled dogs.

When the trail was established there was some hiking going on, but dog teams did the far majority of transport on this trail system. A total of 57 ton of gold came out of Iditarod (approx.52000 kg / 114000 pounds), worth some $30 million. Dog teams hauled most all of that! Along with the mail, supplies and equipment.

The gold rush faded and in the 1920’s dogsled transportation was challenged by the new technology of the airplane. On February 21, 1924, the first Alaskan airmail flew into McGrath on the Iditarod Trail. However in the winter of 1925 the plan to move life-saving serum to Nome onboard airplane was deemed too risky. Instead serum from Anchorage was rushed by train to Nenana on the frozen Yukon River, from where a relay of 20 dog teams took it to Nome in just over 127 hours. The mushers became heroes. President Coolidge sent medals, and Balto, the dog leading the last team into Nome, was used as a model for statues of dogs in places as distant as New York City’s Central park. But Balto was just one of all the sled dog super heroes that made this happen—Togo was another…

The airplane did however take over from the sled dogs; the end of the 1920s established regular mail service by plane to Nome. The Iditarod Trail and dogsledding, along with Alaska’s gold rush frontier era was fading away.

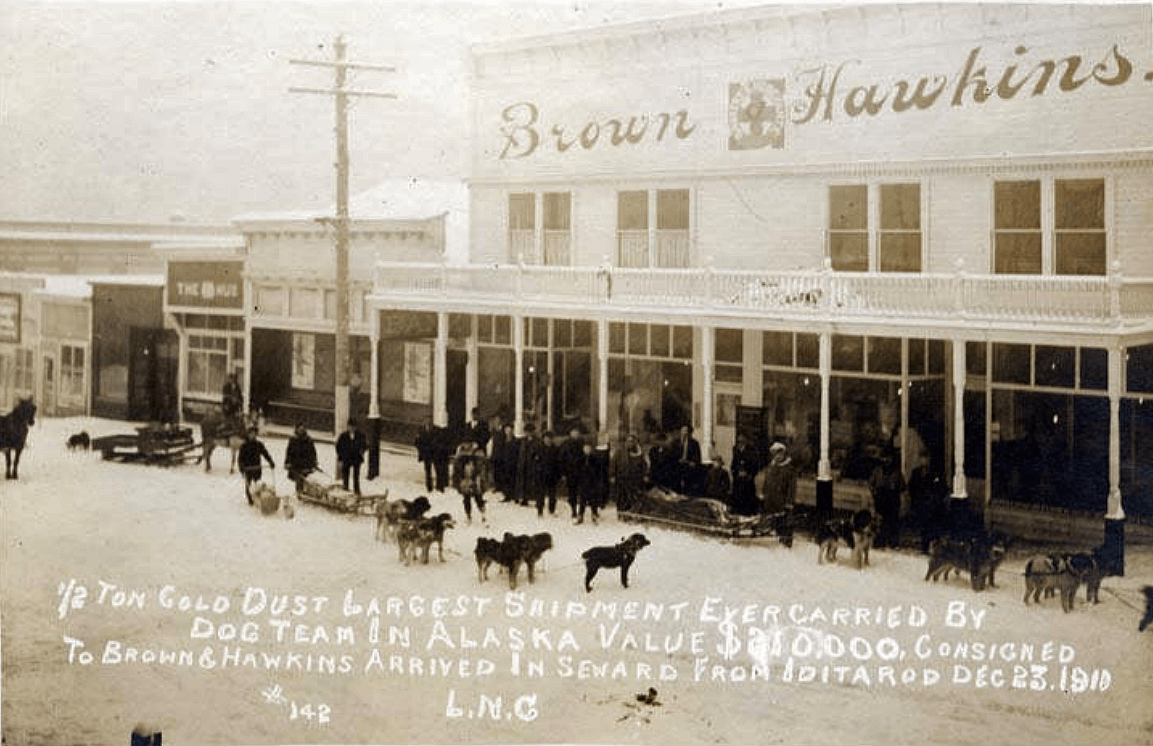

Sled dog teams in Seward, Alaska bringing ½ a ton of gold dust in from the Iditarod gold fields—the largest shipment ever carried by dog team in Alaska value $210,000.

Forest and tundra reclaimed the Iditarod Trail for almost a half a century until Alaskans, led by Joe Redington Sr., reopened the routes. To draw attention to the critical role sled dogs played in Alaska's history – traditionally for eons as well as in the settlement and development of frontier Alaska – Redington set out to create an epic sled dog race from Anchorage to Nome. In 1973 the first Iditarod sled dog race took place, ultimately reviving the Iditarod trail along with dog mushing in Alaska and around the world. After years of effort by Redington and the Alaska Congressional delegation, US Congress designated the Iditarod trail as a National Historic Trail in 1978. Still today, every year significant trail work is done in collaboration between the Iditarod Race Committee and the Iditarod Historic Trail Alliance to keep improving the trail and keeping its history and usage alive.

“Trail Work is never done.”